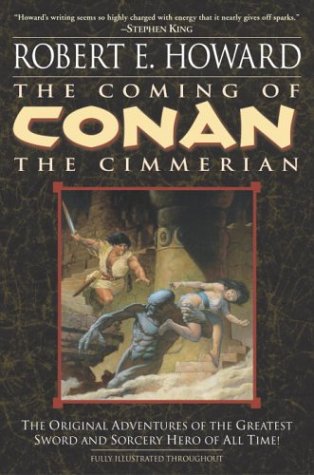

The Legends of Literature Part 3

Too Many Martinis at Lunch, Old Man Potter, Unwise...

Fiction: Susan Spelling B.

The Yawn-Inducing Films of Stanley Kubrick

Five Questions About: Loyalty

Legends of Literature Part 2

Two Poems by Salvatore Antonio Cavataio

Movie vs. Novel

The Rage of Autumn

Literary Criticism

Fantastically Bad Cinema

Essays

Under God's Right Arm

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

January 2008

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

January 2009

February 2009

March 2009

Alcoholic Poet

Baby Got Books

Beaman's World

BiblioAddict

Biblio Brat

Bill Crider's Pop Cultural Magazine

The Bleeding Tree

Blog Cabins: Movie Reviews

A Book Blogger's Diary

BookClover

Bookgasm

Bookgirl's Nightstand

Books I Done Read

Book Stack

The Book Trib

Cold Hard Football Facts

Creator of Circumstance

D-Movie Critic

The Dark Phantom Review

The Dark Sublime

Darque Reviews

Dave's Movie Reviews

Dane of War

David H. Schleicher

Devourer of Books

A Dribble of Ink

The Drunken Severed Head

Editorial Ass

Emerging Emma

Enter the Octopus

Fatally Yours

Flickhead

The Genre Files

The Gravel Pit

Gravetapping

Hello! Yoshi

HighTalk

Highway 62

The Horrors Of It All

In No Particular Order

It's A Blog Eat Blog World

Killer Kittens From Beyond the Grave

The Lair of the Evil DM

Loose Leafs From a Commonplace

Lost in the Frame

Little Black Duck

Madam Miaow Says

McSweeney's

Metaxucafe

Mike Snider on Poetry

The Millions

Moon in the Gutter

New Movie Cynics Reviews

Naked Without Books

A Newbie's Guide to Publishing

New & Improved Ed Gorman

9 to 5 Poet

No Smoking in the Skull Cave

Orpheus Sings the Guitar Electric

Polly Frost's Blog

Pop Sensation

Raincoaster

R.A. Salvatore

Reading is My Superpower

Richard Gibson

SciFi Chick

She Is Too Fond Of Books

The Short Review

Small Crimes

So Many Books

The Soulless Machine Review

Sunset Gun

That Shakesperherian Rag

Thorne's World

The Toasted Scrimitar

This Distracted Globe

Tomb It May Concern

2 Blowhards

Under God's Right Arm

A Variety of Words

The Vault of Horrr

Ward 6

When the Dead Walk the Earth

The World in the Satin Bag

Zoe's Fantasy

Zombo's Closet of Horror

Bookaholic Blogring

Power By Ringsurf

DaRK PaRTY: First, let's talk about Shakespeare the man. Mark Twain once compared Shakespeare's biography to putting together a dinosaur from a few scraps of bone adhered together with plaster. What do we really know about the Bard?

Jennifer: Well, Schoenbaum has written an excellent biography, “Shakespeare's Lives,” which is put together with sound scholarship, and which does a fine job of knitting up the existing bones into a pleasant skeleton. We know that Shakespeare was a successful entrepreneur with some acting ability, who cared a good deal about property and money, and left his older wife his second-best bed (probably not a bad inheritance, however it sounds).

DP: What do you think is the biggest misconception about Shakespeare?

Jennifer: In short, that he wasn't himself. I find these various theories, such as the idea that Marlowe was Shakespeare, or, on the other side, that Shakespeare was in fact the Earl of Oxford, or Fr ancis Bacon, or whomever, silly and tiresome. The second biggest misconception -- though you didn't ask -- is that he didn't write any prose, when he was probably the finest prose writer in Renaissance England: for instance, much of “Henry IV” is prose, and “Hamlet,” like many of the plays, shifts between prose and verse in compelling ways, creating a perfect rhythm, a new sound.

ancis Bacon, or whomever, silly and tiresome. The second biggest misconception -- though you didn't ask -- is that he didn't write any prose, when he was probably the finest prose writer in Renaissance England: for instance, much of “Henry IV” is prose, and “Hamlet,” like many of the plays, shifts between prose and verse in compelling ways, creating a perfect rhythm, a new sound.

DP: As an introduction to Shakespeare which play would you recommend first and why?

DP: Yale professor and literary critic Harold Bloom is fond of saying that Shakespeare created characters more real than living human beings. Which three Shakespearean characters do you consider the most alive and why?

DP: Which three of Shakespeare's plays are your favorites and why?

Read our essay "The Undiscovered Country" here

Read our interview about Charles Dickens here

Labels: 5 Questions, Jennifer Formichelli, Shakespeare

StumbleUpon |

StumbleUpon |

del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |

Technorati |

Technorati |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

The Template is generated via PsycHo and is Licensed.