New DaRK

Ted Haggard’s Letter to his Congregation (As Edite...The Legends of Literature -- Part 1

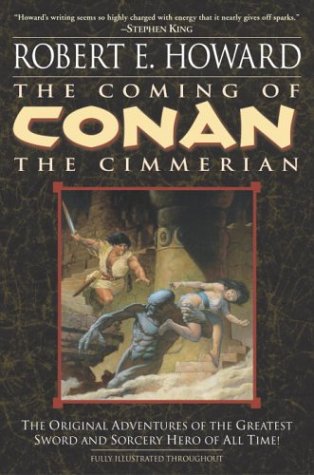

Under God's Right Arm: The Satanic Appeal of Comic...

Fiction: Tantalus

Quoth the Werewolf: Nevergood!

Literary Criticism: Roald Dahl’s “Lamb to the Slau...

10 Greatest Cover Songs

5 Questions About: Laurie Foos

Batman Wises Up

Essay: Employee Bill of Rights

Our Ongoing Features

5 Questions AboutLiterary Criticism

Fantastically Bad Cinema

Essays

Under God's Right Arm

Archive

May 2006June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

January 2008

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

January 2009

February 2009

March 2009

Twitter

DaRK PaRTY NeTWORK

Arcanum CafeAlcoholic Poet

Baby Got Books

Beaman's World

BiblioAddict

Biblio Brat

Bill Crider's Pop Cultural Magazine

The Bleeding Tree

Blog Cabins: Movie Reviews

A Book Blogger's Diary

BookClover

Bookgasm

Bookgirl's Nightstand

Books I Done Read

Book Stack

The Book Trib

Cold Hard Football Facts

Creator of Circumstance

D-Movie Critic

The Dark Phantom Review

The Dark Sublime

Darque Reviews

Dave's Movie Reviews

Dane of War

David H. Schleicher

Devourer of Books

A Dribble of Ink

The Drunken Severed Head

Editorial Ass

Emerging Emma

Enter the Octopus

Fatally Yours

Flickhead

The Genre Files

The Gravel Pit

Gravetapping

Hello! Yoshi

HighTalk

Highway 62

The Horrors Of It All

In No Particular Order

It's A Blog Eat Blog World

Killer Kittens From Beyond the Grave

The Lair of the Evil DM

Loose Leafs From a Commonplace

Lost in the Frame

Little Black Duck

Madam Miaow Says

McSweeney's

Metaxucafe

Mike Snider on Poetry

The Millions

Moon in the Gutter

New Movie Cynics Reviews

Naked Without Books

A Newbie's Guide to Publishing

New & Improved Ed Gorman

9 to 5 Poet

No Smoking in the Skull Cave

Orpheus Sings the Guitar Electric

Polly Frost's Blog

Pop Sensation

Raincoaster

R.A. Salvatore

Reading is My Superpower

Richard Gibson

SciFi Chick

She Is Too Fond Of Books

The Short Review

Small Crimes

So Many Books

The Soulless Machine Review

Sunset Gun

That Shakesperherian Rag

Thorne's World

The Toasted Scrimitar

This Distracted Globe

Tomb It May Concern

2 Blowhards

Under God's Right Arm

A Variety of Words

The Vault of Horrr

Ward 6

When the Dead Walk the Earth

The World in the Satin Bag

Zoe's Fantasy

Zombo's Closet of Horror

Bookaholic Blogring

Power By Ringsurf

Tuesday, November 07, 2006

The Rage of Autumn

In the fading light of the late afternoon, I paused among the crinkled, honey-colored maple leaves scattered on my driveway. Overhead, between the dark boughs of a large tree, the full moon – glistening like a silver fish – dominated the sky. The sight of it – its confidence – its defiance of the day – broke my stride.

In the fading light of the late afternoon, I paused among the crinkled, honey-colored maple leaves scattered on my driveway. Overhead, between the dark boughs of a large tree, the full moon – glistening like a silver fish – dominated the sky. The sight of it – its confidence – its defiance of the day – broke my stride.There was a hint of ice in the air, enough so your lungs understood that winter was coming – sooner rather than later. The sky was a cloudless tapestry of blue, a rarity in New England during November when the sky usually looks like a dirty pie plate.

Autumn is the season for reflection. When time seems to slow down and the activities of summer are put away like tools in an old shed. It is a strange season – one of death and decay combined with brilliant colors and striking beauty. It is as if the trees collectively decide to give us a last gasp of merriment before falling dormant until the spring.

No other season makes you reflect so much on your own mortality. I found myself frozen to the driveway – gazing at the bold moon – thinking about my grandfather who died when I was a baby. His wedding ring now adorns my own ring finger and I gazed down on it as I’m apt to do when thinking about him.

That brought on thoughts of my own father and his battle with prostate cancer. A fight he has been winning; taken on with grim determination and his typical quiet stoicism which he inherited from my grandfather. Neither man was one for complaints – for whining. My father is a big, tough man, but tender to those he loves, especially to his grandchildren (whom he adores like a big old bear).

I realize that my father remains my safety net. If I fall, if I fail, even as I slide into middle age, he will be there to catch me. I can rely on his guidance, his sometimes gruff instructions on how I need to weatherproof the windows or how best to winterize the flower garden. He doesn’t advise, my father, he tells. At times, I feel my temper rise or the heat in my cheeks, but mostly I know he is right. This, I’ve come to understand, is how my father tells me he cares.

I like knowing that my father stands behind me – his big mitt of a hand on my shoulder. I like that he cares about the length of the grass on my lawn and knows the best way to clean out gutters.

I like that he has been strong enough to beat the cancer that tried to take him down. And that’s why I always think of my father when I read Dylan Thomas’s most famous poem; a poem that perfectly reflects a vibrant fall day when the moon decides to capture the day.

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Labels: Autumn, death, Dylan Thomas, Poetry

StumbleUpon |

StumbleUpon |

del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |

Technorati |

Technorati |

0 Comments:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

The Template is generated via PsycHo and is Licensed.