Essay: What War?

Movie Swiping, Scene-Chomping Comedic Performances

5 Questions About: Dirty Harry

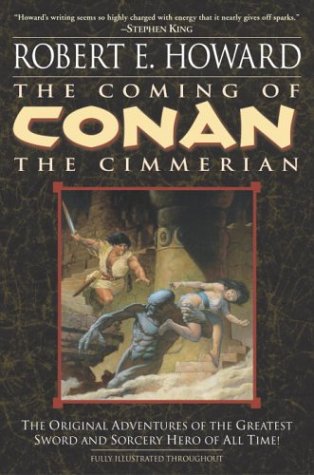

Cracked-Back Book Reviews: June 2007

Poem: Shut Up

The Short, Short Story Winners

Under God's Right Arm: Gays Take Massachusetts

'Nuf Said: The Best and Worst of Superhero Movies

5 Questions About: Friday the 13th

Literary Criticism

Fantastically Bad Cinema

Essays

Under God's Right Arm

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

January 2008

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

January 2009

February 2009

March 2009

Alcoholic Poet

Baby Got Books

Beaman's World

BiblioAddict

Biblio Brat

Bill Crider's Pop Cultural Magazine

The Bleeding Tree

Blog Cabins: Movie Reviews

A Book Blogger's Diary

BookClover

Bookgasm

Bookgirl's Nightstand

Books I Done Read

Book Stack

The Book Trib

Cold Hard Football Facts

Creator of Circumstance

D-Movie Critic

The Dark Phantom Review

The Dark Sublime

Darque Reviews

Dave's Movie Reviews

Dane of War

David H. Schleicher

Devourer of Books

A Dribble of Ink

The Drunken Severed Head

Editorial Ass

Emerging Emma

Enter the Octopus

Fatally Yours

Flickhead

The Genre Files

The Gravel Pit

Gravetapping

Hello! Yoshi

HighTalk

Highway 62

The Horrors Of It All

In No Particular Order

It's A Blog Eat Blog World

Killer Kittens From Beyond the Grave

The Lair of the Evil DM

Loose Leafs From a Commonplace

Lost in the Frame

Little Black Duck

Madam Miaow Says

McSweeney's

Metaxucafe

Mike Snider on Poetry

The Millions

Moon in the Gutter

New Movie Cynics Reviews

Naked Without Books

A Newbie's Guide to Publishing

New & Improved Ed Gorman

9 to 5 Poet

No Smoking in the Skull Cave

Orpheus Sings the Guitar Electric

Polly Frost's Blog

Pop Sensation

Raincoaster

R.A. Salvatore

Reading is My Superpower

Richard Gibson

SciFi Chick

She Is Too Fond Of Books

The Short Review

Small Crimes

So Many Books

The Soulless Machine Review

Sunset Gun

That Shakesperherian Rag

Thorne's World

The Toasted Scrimitar

This Distracted Globe

Tomb It May Concern

2 Blowhards

Under God's Right Arm

A Variety of Words

The Vault of Horrr

Ward 6

When the Dead Walk the Earth

The World in the Satin Bag

Zoe's Fantasy

Zombo's Closet of Horror

Bookaholic Blogring

Power By Ringsurf

My silver car streaked down the highway. Van Halen’s “Everybody Wants Some!!” pounded out the car speakers. With the windows rolled down, the warm twilight rushed through the interior, whipping my hair. I was speeding, but the sensation of freedom was too great and the music too loud to slow down.

But then a red light and I was forced to hit the brakes. At the side of the road was a beggar; young guy with a scruffy beard, bleary red-rimmed eyes, and a baggy navy-blue sweatshirt marred by several stains. He held a sign, but I couldn’t make it out.

On impulse, I pulled out my wallet and handed him a five-dollar bill. He smiled and with a nod said: “God bless you.”

I wanted to tell him there is no god, but we both understood that he wasn’t being literal. He was being gracious – and a bit disingenuous, but he was playing his role and I was playing mine.

The light flicked green and I roared off. But I was already contemplating Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty, the two protagonists of Jack Kerouac’s 1957 classic “On the Road,” which turns half-a-century old this year. I wondered if my beggar was grooving on his freedom – silently laughing at me as I returned to the chains of my own conventional life.

It was that thought that finally slowed me down. I began to ponder on the mysterious power of freedom and how “On the Road” may have captured that spirit better than any other novel in the last 100 years.

“On the Road” might be turning middle aged, but the novel remains as energetic and vibrant as a 21-year-old hitchhiking across the

Many critics have belatedly praised the book fro its influence on modern writers, rock music, and even movies, but they seem to do so begrudgingly. They like to point out the flaws of the novel – its jerky narrative and uneven flow; its revolving door of minor and insignificant characters. But to do so is to miss the point of “On the Road.”

The novel is a subversive classic – a work fiction that shattered the conventions of post-World War II America and read like a fast-paced jazz tune played in a smoky roadhouse. While the government and mass media were busy praising our unprecedented war victory and urging Americans to get back to work, settle down in a nice little bungalow, and raise law-abiding children, Kerouac was there to remind us that not everyone wanted to be part of that program. He boldly told us that victory over

Kerouac screamed that messages to the heavens. He flipped his middle fingers at traditional American values and reminded us that there was more to life than a dreary 9 to 5 existence with church on Sunday. “On the Road” is about the search for independence – a quest for free will. It is about following emotions – letting the little demons of our souls loose every once in a while.

The New York Times Book Review called “On the Road” the “Huckleberry Finn” of the 20th century – but even that lofty comparison misses the mark. “On the Road” isn’t following in the footsteps of “Huckleberry Finn” – it blazed its own way to become something completely different.

The novel is stunningly iconoclastic. It is men speeding across the desert in the nude to feel the hot wind whipping across their sweaty chests. It is threesomes having sex together to experiment and explore. It is dive bars filled with jazz musicians and spectators smoking pot and grooving to the music. It is educated men turning their backs on respectability and living like bums.

As Kerouac writes: “The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a common place thing, but burn burn burn, like fabulous yellow Roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”

Perhaps one of the most overlooked and amazing characters in the book in Dean Moriarty’s girlfriend (and sometime wife) Marylou. Can you imagine the courage of this woman? In a time when women were often considered indentured servants – she was whizzing across the

How terrifying for

“On the Road” continues to rage. It continues to push convention even 50 years later.

It’s much more effective capturing the essence of freedom than speeding down a highway listening to rock music.

How is that for lasting power?

Labels: "On the Road", books, Jack Kerouac, literature

StumbleUpon |

StumbleUpon |

del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |

Technorati |

Technorati |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

The Template is generated via PsycHo and is Licensed.