Billy, Lose This Music Video

Strange Fruit: The Making of a Protest Song

5 Questions About: Star Wars

Essay: On Mowing the Lawn

An Atheist Watches "The Passion of the Christ"

5 Questions About: Documentary Films

Under God's Right Arm: The Glorious Rev. Falwell

"Maus" Revisited

Fantastically Bad Cinema: Music & Lyrics

Literary Criticism

Fantastically Bad Cinema

Essays

Under God's Right Arm

June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

January 2008

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

January 2009

February 2009

March 2009

Alcoholic Poet

Baby Got Books

Beaman's World

BiblioAddict

Biblio Brat

Bill Crider's Pop Cultural Magazine

The Bleeding Tree

Blog Cabins: Movie Reviews

A Book Blogger's Diary

BookClover

Bookgasm

Bookgirl's Nightstand

Books I Done Read

Book Stack

The Book Trib

Cold Hard Football Facts

Creator of Circumstance

D-Movie Critic

The Dark Phantom Review

The Dark Sublime

Darque Reviews

Dave's Movie Reviews

Dane of War

David H. Schleicher

Devourer of Books

A Dribble of Ink

The Drunken Severed Head

Editorial Ass

Emerging Emma

Enter the Octopus

Fatally Yours

Flickhead

The Genre Files

The Gravel Pit

Gravetapping

Hello! Yoshi

HighTalk

Highway 62

The Horrors Of It All

In No Particular Order

It's A Blog Eat Blog World

Killer Kittens From Beyond the Grave

The Lair of the Evil DM

Loose Leafs From a Commonplace

Lost in the Frame

Little Black Duck

Madam Miaow Says

McSweeney's

Metaxucafe

Mike Snider on Poetry

The Millions

Moon in the Gutter

New Movie Cynics Reviews

Naked Without Books

A Newbie's Guide to Publishing

New & Improved Ed Gorman

9 to 5 Poet

No Smoking in the Skull Cave

Orpheus Sings the Guitar Electric

Polly Frost's Blog

Pop Sensation

Raincoaster

R.A. Salvatore

Reading is My Superpower

Richard Gibson

SciFi Chick

She Is Too Fond Of Books

The Short Review

Small Crimes

So Many Books

The Soulless Machine Review

Sunset Gun

That Shakesperherian Rag

Thorne's World

The Toasted Scrimitar

This Distracted Globe

Tomb It May Concern

2 Blowhards

Under God's Right Arm

A Variety of Words

The Vault of Horrr

Ward 6

When the Dead Walk the Earth

The World in the Satin Bag

Zoe's Fantasy

Zombo's Closet of Horror

Bookaholic Blogring

Power By Ringsurf

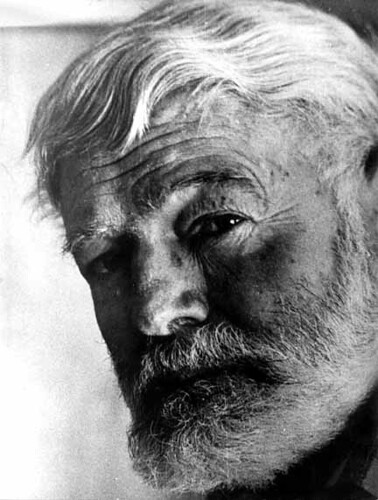

Analysis: James Joyce once said: “Hemingway has reduced the veil between literature and life, which is what every writer strives to do. Have you read “A Clean Well-Lighted Place”? It is masterly. Indeed, it is one of the best short stories ever written.”

It would be difficult to argue with Joyce.

“A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” is an intake of breath. It fills your lungs with icy air, expanding, the sharpness prickling your chest, and then it emerges as a sigh -- a lonely, forlorn sound of utter despair.

“A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” is about the fear of death – our collective terror at the shadows that surround the edges of life. It is about loneliness and emptiness and feeling like no one understands you or even cares to understand you. It is about the inability of human beings to connect with each other.

Hemingway’s critics – and there are many – fail to separate the man from the artist. Hemingway the man became a buffoon; a performer on the world stage who at the end of his life became a parody of himself. But Hemingway the artist was genius, but you need to remove the myth of the man from the beauty of his prose.

Hemingway wrote about a dozen novels, but his short stories are where his concise, economical style shone through. He was a master of the unspoken – evoking powerful emotions from what was being said between the lines. “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” is just such a work. On the surface, the story is about two waiters and an old man; a simple, even mundane, portrait of a few hours at a café along a dirt road.

But there is so much more lingering at the edges, crackling in the dialogue, and in the way Hemingway captures the humanity of his characters. The stage is set in the opening lines of “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.”

“It was late and every one had left the café except an old man who sat in the shadow the leaves of the tree made against the electric light. In the day time the street was dusty, but at night the dew settled the dust and the old man like to sit late because he was deaf and now at night it was quiet and he felt the difference.”

The young waiter is impatient – a cocky young man with a job, a wife, and a lot of confidence. He is frustrated that the old man sits at the café drinking all night long; keeping him at his post when he’d rather be sleeping next to his wife. He fails to understand that the old man comes to café for solace – it is a safe haven against the cruelties of life and his pending death.

The older waiter understands it perfectly. He is the old man’s kindred spirit. “You do not understand,” he tells the younger waiter. “This is a clean and pleasant café. It is well lighted. The light is very good and also, now, there are shadows of the leaves.”

Yes, the older waiter is saying, here is life and safety, but even here we will be reminded of death.

Hemingway takes “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” a step further as the older waiter goes to a bar for a night cap. He recites the “Lord’s Prayer” to himself and replaces all the nouns with the Spanish word “nada” – nothing. It is a kick in the teeth to religion – an acknowledgement by Hemingway that there is no great beyond – no clean, well-lighted place after life ends.

There is only nothingness.

The story ends like a heart-wrenching melody: “Now, without thinking further, he would go home o his room. He would lie in the bed and finally, with daylight, he would go to sleep. After all, he said, to himself, it is probably only insomnia. Many must have it.”

Read our literary sketch of Hemingway’s “Indian Camp”

Labels: Hemingway, literary criticism, literature

StumbleUpon |

StumbleUpon |

del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |

Technorati |

Technorati |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

The Template is generated via PsycHo and is Licensed.