New DaRK

5 Questions About: Getting PublishedThe 12 Best Actresses in Hollywood

Book Review: It's the End of the World As We Know It

12 Signs That You Might Have Been Laid-Off

Winner of OUTLIERS Giveaway Announced!

5 Questions About: Horror Movies

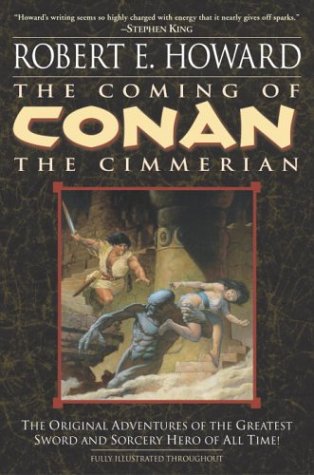

The Toughest SOBs in Fantasy Fiction

Fantastically Bad Cinema: Tropic Thunder

Thoughts from the Shadows: The Thompson Question

Michael Connelly Book Winners Announced!

Our Ongoing Features

5 Questions AboutLiterary Criticism

Fantastically Bad Cinema

Essays

Under God's Right Arm

Archive

May 2006June 2006

July 2006

August 2006

September 2006

October 2006

November 2006

December 2006

January 2007

February 2007

March 2007

April 2007

May 2007

June 2007

July 2007

August 2007

September 2007

October 2007

November 2007

December 2007

January 2008

February 2008

March 2008

April 2008

May 2008

June 2008

July 2008

August 2008

September 2008

October 2008

November 2008

December 2008

January 2009

February 2009

March 2009

Twitter

DaRK PaRTY NeTWORK

Arcanum CafeAlcoholic Poet

Baby Got Books

Beaman's World

BiblioAddict

Biblio Brat

Bill Crider's Pop Cultural Magazine

The Bleeding Tree

Blog Cabins: Movie Reviews

A Book Blogger's Diary

BookClover

Bookgasm

Bookgirl's Nightstand

Books I Done Read

Book Stack

The Book Trib

Cold Hard Football Facts

Creator of Circumstance

D-Movie Critic

The Dark Phantom Review

The Dark Sublime

Darque Reviews

Dave's Movie Reviews

Dane of War

David H. Schleicher

Devourer of Books

A Dribble of Ink

The Drunken Severed Head

Editorial Ass

Emerging Emma

Enter the Octopus

Fatally Yours

Flickhead

The Genre Files

The Gravel Pit

Gravetapping

Hello! Yoshi

HighTalk

Highway 62

The Horrors Of It All

In No Particular Order

It's A Blog Eat Blog World

Killer Kittens From Beyond the Grave

The Lair of the Evil DM

Loose Leafs From a Commonplace

Lost in the Frame

Little Black Duck

Madam Miaow Says

McSweeney's

Metaxucafe

Mike Snider on Poetry

The Millions

Moon in the Gutter

New Movie Cynics Reviews

Naked Without Books

A Newbie's Guide to Publishing

New & Improved Ed Gorman

9 to 5 Poet

No Smoking in the Skull Cave

Orpheus Sings the Guitar Electric

Polly Frost's Blog

Pop Sensation

Raincoaster

R.A. Salvatore

Reading is My Superpower

Richard Gibson

SciFi Chick

She Is Too Fond Of Books

The Short Review

Small Crimes

So Many Books

The Soulless Machine Review

Sunset Gun

That Shakesperherian Rag

Thorne's World

The Toasted Scrimitar

This Distracted Globe

Tomb It May Concern

2 Blowhards

Under God's Right Arm

A Variety of Words

The Vault of Horrr

Ward 6

When the Dead Walk the Earth

The World in the Satin Bag

Zoe's Fantasy

Zombo's Closet of Horror

Bookaholic Blogring

Power By Ringsurf

Monday, December 15, 2008

Book Review: "The Brass Verdict" Plays It Safe

Author Michael Connelly Avoids Risks, Yet "The Brass Verdict" a Satisfying Crime Novel

Michael Connelly is a safe bet. Pick up one of his crime novels and you’re going to get a tight-plotted caper with colorful characters, riveting dialog, and a satisfying conclusion.

That’s why Connelly is a blockbuster author and New York Times bestseller. He’s consistent – consistently good.

But after more than 20 novels, this consistency may be starting to become something worse: predictable. Case in point: “The Brass Verdict.”

“The Brass Verdict” is the second novel in Connelly’s new series about Mickey Haller, a defense lawyer in Los Angeles. Haller is an interesting character – a former addict to painkillers who keeps his emotions tightly contained. He’s a brutal realist, but with a soft spot for certain hard luck cases.

The character (and the series) shows a lot of promise. Connelly has a great eye for criminal case detail and understands how to create courtroom suspense. The best parts of “The Brass Verdict” are all in the courtroom.

It’s unfortunate that Connelly didn’t feel confident enough to allow Haller’s case to unfold. The story is a good one. Haller, recently out of rehab, inherits the caseload of a fellow defense attorney. One of the clients is a rich and powerful movie mogul accused of murdering his wife and her lover.

Walter Elliot is an arrogant, oily tycoon with a likability score of less than zero. But did he shoot and kill two people?

Haller isn’t interested in guilty or innocence – only in building a case that can win. This razor-thin line that Haller walks as he investigates the homicides makes for a fascinating look at his character and at how our criminal justice system works.

This is how Connelly opens the novel: “Everybody lies. Cops lie. Lawyers lie. Witnesses lie. The victim lies. A trial is a contest of lies. And everyone in the courtroom know this.”

If only Connelly let Haller build his case and kept us in the courtroom as he argued and maneuvered. The novel would have been even better.

Unfortunately, “The Brass Verdict” gets the same treatment as Connelly’s first breakout bestseller “The Poet” (1996). There are more twists here than an Olympic high-platform dive – and in the end – there’s just too many to keep the story believable.

Part of the problem is the presence of L.A. Police Detective Harry Bosch. Bosch is Connelly’s primary series character (and if you haven’t read any of the books featuring Bosch – you really should).

Bosch really doesn’t have a role in “The Brass Verdict” – except as a crossover concept (and for a surprise coincidence at the end). Bosch’s investigation into Elliot’s alleged double homicide is more of distraction than an addition. It keeps us out of the courtroom – where the real action is.

But even with Connelly’s decision to use Bosch and play twister at the end – “The Brass Verdict” is better than most of the mainstream crime fiction out there. You have to hand it to Connelly – his formula for consistency keeps him selling books.

It would be nice to see him take some risks and move away from his modus operandi, but then again why mess with success?

Buy "The Brass Verdict" at Amazon.com

Read our Review of Ken Bruen's "The Guards"

The 5 Scariest Stephen King novels

Knock Your Socks Off Good Books

Labels: book review, Michael Connelly, The Brass Verdict

StumbleUpon |

StumbleUpon |

del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |

Technorati |

Technorati |

0 Comments:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 License.

The Template is generated via PsycHo and is Licensed.